Has this ever happened to you? Driving around in the country, you pass a big red sofa at the end of someone’s driveway with a sign on it: “Take Me! I’m Free!” Why not take it home? After all, it is free.

Everything we know about economics suggests that everyone should want something if it does not cost anything. For most of us, however, that inclination is quick to pass, replaced by more pragmatic assessments: We really do not need another sofa because we already have more sofas than we can use, we really do not want red furniture of any kind, and we will have to dispose of this beast if it does not work out as well as we have imagined.

Similarly, banks each week pass by the ECB’s repo window, where the central bankers put out an unlimited amount of cash for free. Only a couple dozen of the nearly 8,000 financial institutions eligible to take this money do so, and only sparingly. Apparently, cash is like that red sofa nobody needs or wants: Even for free, it is not in great demand.

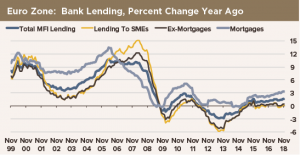

What does it mean for an economy when no one will take free money from the central bank? Keynes had a view on this, one we refer to as “the liquidity trap.” Banks’ demand for liquidity is exactly equal to the new cash balances the ECB is creating with its asset purchases: Constrained by capital ratios and regulation, banks are unable to lend more, and therefore have no use for incremental reserves.

To bring the red sofa metaphor fully around to the current economic situation in Europe, we can say that banks’ unwillingness to pick up that sofa from the end of the driveway is symptomatic of a condition where lending is impossible, companies and households are hoarding the liquidity being created by the monetary authorities, and therefore economic recovery is getting no push from monetary expansion.

In our view, Europe has the potential to enjoy an export-led recovery in 2018 as trade with China pulls the economy out of its liquidity trap. That pull is needed to get companies to invest in new capacity—creating jobs, income and spending along the way. However, banks have to start lending again to turn this tepid economic expansion into a robust economic recovery. That may require some relaxation of regulation, or capital inflows from abroad—from places like China, with plenty of excess savings – or an increase in bank capital to bolster weak domestic lending.

We will know that recovery has been truly achieved – that growth is sustained above its potential rate—when the demand for big red sofas exceeds supply: When banks start using reserves rather than hoarding them, and the price of money starts going up. We fear that we are still some way away from that point.