It is time to review the factors that have led China’s growth rate to slow since 2008, and with increased vigor since Xi Jinping became president in 2013 and reoriented economic policies away from domestic GDP growth toward global economic ambitions. Key ingredients of growth in a developing economy are demographics, productivity and investment, as a driver of productivity.

It is time to review the factors that have led China’s growth rate to slow since 2008, and with increased vigor since Xi Jinping became president in 2013 and reoriented economic policies away from domestic GDP growth toward global economic ambitions. Key ingredients of growth in a developing economy are demographics, productivity and investment, as a driver of productivity.

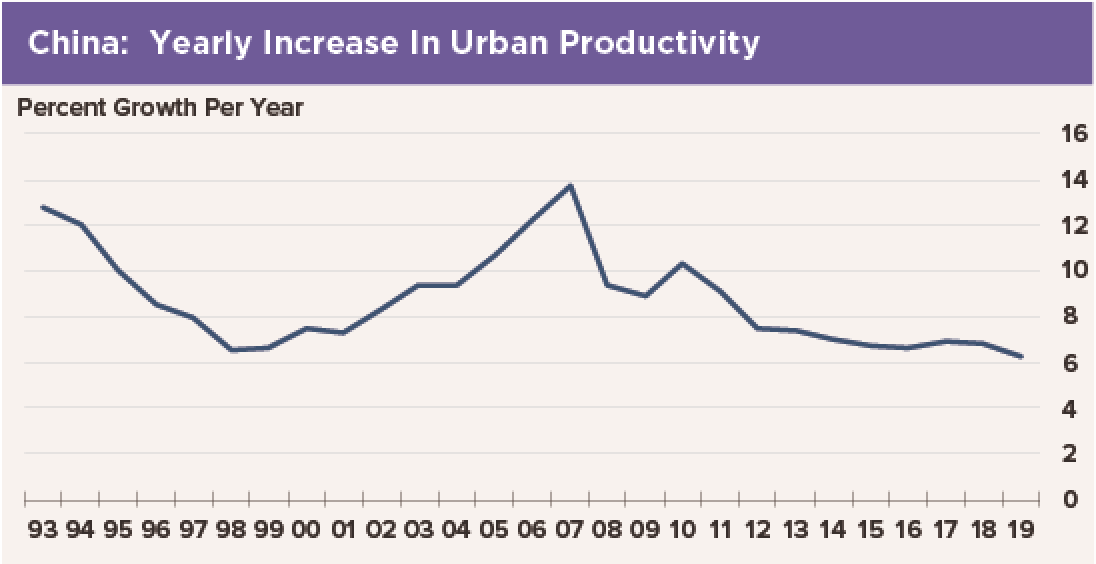

For the first 10 years of HFE’s Weekly Notes on China’s Economy, the only way to think about China’s then 8%-plus GDP growth rates was to understand the demographic dividend. In an accelerated burst of modernization, China’s urban population increased by two thirds over 20 years to 606 million people. Almost all of that increase was due to migration of people from farms to cities. Almost all of that migration was adult workers, leaving subsistence-wage jobs in the agricultural sector for higher-productivity, manufacturing/assembly jobs in the city. In round numbers, moving a person from the farm to the city increased his or her average wage five-fold, but output per worker rose tenfold.

Because there was an abundance of workers able to leave the agricultural sector—thanks to decreased infant mortality rates and advances in farm productivity—China’s urban sector was able to grow with a “seemingly unlimited supply of labor,” a development phase described by St. Lucia’s 1979 Nobel Laureate Arthur Lewis. Companies find it infinitely profitable to grow by offering workers wages well in excess of their subsistence farm wage but well below their marginal product. The resulting profits are, in theory, reinvested in growth and employment, generating even more economic growth.

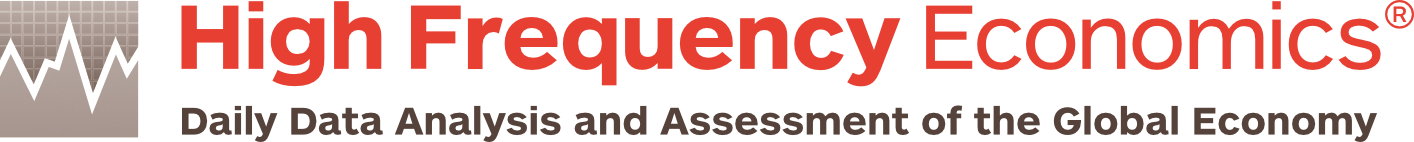

In China’s case, 10% GDP growth on average was driven in this 20-year period by 4%-or-faster growth of the urban population and urban productivity gains ranging from 6% to 14% per year. Lewis and his followers warned that countries experiencing growth on this “seemingly unlimited” fast track were in fact limited in their growth potential in the longer run. The population might continue to grow at a steady rate, but over time increases would decline as a percentage of the urban population. Second, the number of workers that could be freed from the agricultural sector is limited—someone has produce the food, eh? Third, the marginal product of labor decreases as workers are added to the urban economy. Thus the dividend from shifting workers from the farm to the city decreases.

All of this has happened in China’s case. As our charts shows, about 20 million people are still moving into China’s cities each year. However, as a share of the urban population, that number has dropped to 2% per year from 4-1/2% two decades ago. At the same time, productivity of urban workers continues to grow, but at a lower pace. Farm productivity has increased. So the “dividend” from moving a worker to the city from the farm has decreased.

President Xi’s policy approach is also significant. China has become more focused on projecting economic power to emerging-economy allies under his stewardship. Money spent to build a rail line from Turkmenistan to Tajikistan does not add as much to China’s GDP growth as money spent to build an identical rail line from Ürümqi to the border. However, China’s investment in the economies of its neighbors increases its economic and political influence in its own back yard, a trade-off of GDP growth for greater political influence.

Thus, GDP growth has dropped to about 6% per year on trend. It is unlikely to pick up a lot from that pace. There is nothing wrong with a 6%-per-year trend growth rate. China’s long-term economic plan calls for a doubling of the size of the economy by 2035. That only requires 5% yearly growth. Meanwhile, it is time to recalibrate our expectations to match China’s outward-looking ambitions: It costs something to win influence over the world, eh?