Part of ECB President Draghi’s job is being a cheerleader for the Euroland economy. Therefore, we can understand why he has to say stuff like this at his press conference:

Part of ECB President Draghi’s job is being a cheerleader for the Euroland economy. Therefore, we can understand why he has to say stuff like this at his press conference:

“The risks surrounding the euro area growth outlook remain tilted to the downside, on account of the prolonged presence of uncertainties, related to geopolitical factors, the rising threat of protectionism and vulnerabilities in emerging markets.”

This has become the way of all policymakers and all central bankers: Whatever is wrong in the economic outlook, the trouble always lies somewhere else.

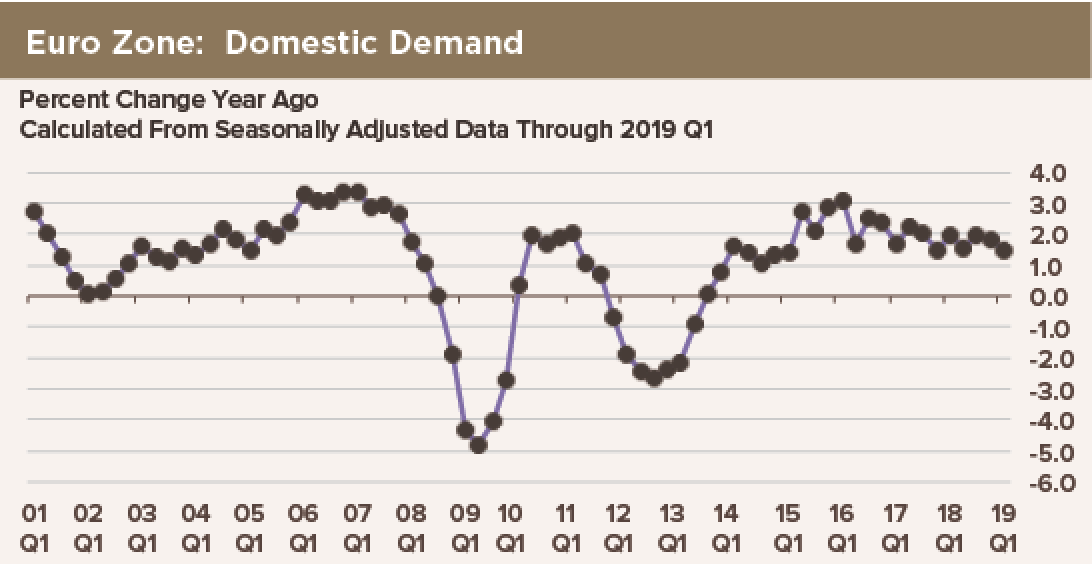

It is not that we do not believe that President Trump’s trade adventurism is denting world trade… it is. It is not that we disbelieve that a crimp in world trade has crimped Euroland’s economic growth. However, our chart shows that the problem with Euroland growth is slowing domestic demand.

Growth of final domestic demand has halved from 3% per year in 2016 to 1.4% in the first quarter. This is total domestic demand, calculated as GDP minus exports plus imports. The real culprit behind the slowdown of domestic demand and GDP is the inventory correction—the domestic inventory correction. Add 1.6 percentage points to year-over-year GDP growth to guess that the economy might be growing just under 3% year-over-year instead of 1.4% if only domestic demand had held up.

At least Dr. Draghi recognizes that near-term prospects are not so hot. Even so, he tells us that inflation metrics should rise and the unemployment rate should continue to fall, in some unspecified timeframe. Really? The economics we learned in school tell us that economic growth that starts at 1.4% per year and decays for another two quarters—dare we say, at least two more quarters?—will not do much to push inflation from around 1% at the core to the 2% target. Neither will it continue to bring down the unemployment rate for very long.

We welcome this inventory correction. It has to happen for Europe to resume industrial and GDP growth. We also accept the hard truth that the ECB has no more tools to throw at the problem of boosting economic growth. Better to acknowledge that—and send a clear message to other policymakers in Europe that fiscal health is needed—than to pretend that incremental stimulus is not needed and that the ECB has it all under control. It does not.

The latest ECB staff forecasts put HICP “inflation” at 1.3% in 2019, 1.4% in 2020 and 1.6% in 2021. Based on the ECB’s guidance, not only are markets promised no increase in interest rates until at least mid-2020, but inflation metrics will still average below target by 0.4 percentage points in 2021. Practically speaking, no one should expect any ECB tightening at all until some time in 2022, as long as guidance and the inflation target are not changed.