Some readers have taken umbrage at our assertion that the jobless rate is a meaningless metric in Germany.

Some readers have taken umbrage at our assertion that the jobless rate is a meaningless metric in Germany.

The economic argument behind this has its basis in development economics, specifically in the work of Nobel Laureate W. Arthur Lewis. He wrote—in 1954—about modernization in an emerging, or developing, economy by shifting workers out of the low-productivity, low-wage agricultural sector into higher-productivity, higher-wage jobs in the industrial sector. Lewis argued that this “demographic dividend” was a critical driver of the rise in income per worker and income per capita in the modernization process. As long as there are enough workers on the farms to move to the cities, income per capita continues to rise.

What does this have to do with Germany? Think of Euroland as two economies—the German economy, where unemployment is negligible, and the rest of Europe, where the jobless rate is 8.9%. That is still two full percentage points higher than it was a dozen years ago, before the economic crash of 2008-09.

If Germany’s borders are open to immigration, unemployed workers can cross freely from the rest of Europe—where their productivity is zero—to take jobs in Germany at wages that are well below the value of their marginal product. This is why the record low German unemployment rate does not reflect a truly tight supply of labor: The vast army of unemployed in the rest of Europe provides Germany with a seemingly unlimited supply of labor. Workers in Germany dare not ask for raises, as they can be replaced by immigrants on the cheap. The addition of low-wage immigrants to the labor force means average wages fall.

When the economy sours, companies shed workers. The marginal worker in the German economy is the immigrant who was the last to be hired. He or she will be the first to be fired, if only because the separation costs are lower. If these workers do not remain in Germany, they will neither receive unemployment benefits nor be counted as unemployed in Germany’s official statistics. Therefore, fluctuations in the unemployment rate might not tell us much about the state of the economy.

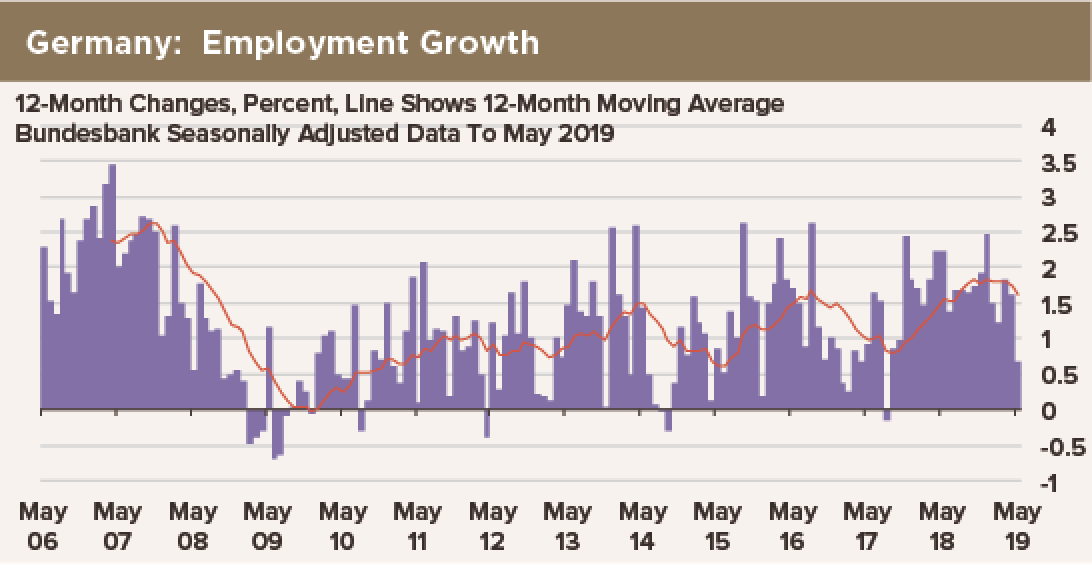

HFE monitors employment growth rates within Germany’s national borders as the best metric for gauging the business cycle position of the economy. Slowing employment is a tell that output is slowing. Falling employment would be a tell that the economy is contracting. However, neither the jobless rate nor the number of unemployed will necessarily respond in tandem with the growth rate of employment.

Thus, we are impressed by the accelerating slowdown in German employment. We do not care that the jobless rate is at an epochal low: It may well remain there even as an economic recession develops.